Whose trees are they anyway

The Appiko movement, which began as a crusade to protect the trees of the Kalse forests in Karnataka 35 years ago, has turned into a continuing battle to save the Western Ghats

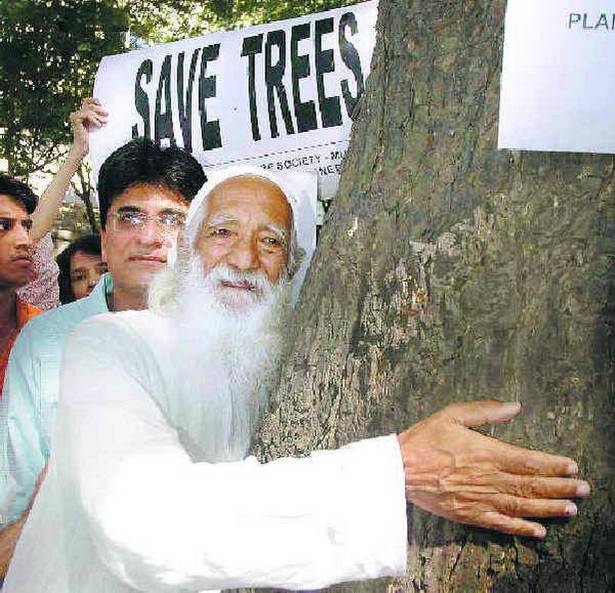

On September 8, 1983, a group of around 70 villagers from the Salkani village of Uttara Kannada district stood hugging the trees of the Kalse forests to prevent them from being felled by state authorities. Founded and led by environmental activist Panduranga Hegde, the movement christened Appiko (“hug” in Kannada, symbolising protection for the tree) became south India’s first large-scale environmental movement. Inspired by the tree-hugging Chipko forest conservation movement in the North, the Appiko movement continues its fight against tree-felling and deforestation in not only Uttara Kannada but also other hill districts in Karnataka and Kerala. The Chipko movement turned 45 recently and its famous slogan, “ecology is permanent economy”, resonates even today. South India’s Chipko, Appiko too has achieved formidable successes.

The forest cover in Uttara Kannada shrank from 80 per cent in 1950 to a mere 25 per cent within 30 years. The systematic introduction of plywood factories, pulp and paper mills, as well as the construction of hydroelectric dams in the region were to blame for the loss of forest cover. The developmental projects not only displaced thousands of indigenous people dependent on the forests for a living, but also sapped natural resources. Hegde states, “Over 30 million people are adversely affected by this phenomenon.” Like Chipko, Appiko too began as a non-violent crusade to secure forest cover and protect the lives of tribal groups dependent on forest resources — an interconnection that is almost entirely ignored in the larger articulations of ‘development’. The significant participation of women is another common feature of both movements. While Sunderlal Bahuguna is acknowledged as the leader of Chipko, the contributions of women such as Gaura Devi, president of the Mahila Mangala Dal, are not to be forgotten either. On the first day of the movement, Gaura Devi and 27 other women stood hugging trees, thus preventing the lumbermen, who had governmental permissions, from felling trees. The Mahila Mandal of Kerehosahalli too extended support to the Appiko movement. Among the protesting villagers of Salkani, nearly 30 were women, and they too stood hugging trees until the axes were dropped and the labourers left in frustration. Despite abuse and slurs, the women stood their ground. The Mahila Mandal comprised women from different castes and tribal groups. In the initial days of the movement, as a contribution, the women would daily keep aside a fistful of grain, which the environmental activists would collect and pass on to those who stood guard for the trees continuously in the forests.

What prompted women to leave safe familial spaces and take on forces representative of the government?

A primary feature of tribal and other communities dependent on forest resources is their close relationship with nature — waterbodies as well as the flora and fauna of specific physiographical spaces. Nature is not only a source of food and livelihood, but also holds deep-rooted cultural meanings that inform and govern tribal sociocultural practices.

Tribal agronomy, including soil management and crop production, is perpetuated through generations by the practise of subsistence agriculture and is considered indigenous knowledge, a source of pride for tribal societies. Owing to indigenous agricultural practices, these societies have traditionally been largely self-reliant, without having to depend on the Public Distribution System. Their diet is rich in nutrition owing to natural ways of production and harvesting, as well as the dominance of protein-rich indigenous grains, finger millets and dryland crops, pulses, oilseeds, fruits, edible flowers, tubers and mushrooms. These are gathered or foraged foods, and women play a major role in their procurement and cooking. Women have a major role in the conservation of this indigenous knowledge and, by extension, the conservation of forest resources.

From caregivers to healers, to food growers to reapers and harvesters, from preservers of indigenous seeds to curation and custodianship of tribal recipes, animal-keeping to firewood and fuel collection, without women, these communities will not be able to sustain or replicate their culture. Yet, what patriarchal potency does to women, it does to nature. Exploit. Subjugate. Oppress.

Nomenclature that describes flora and fauna has been developed based on the needs of human activity for profit. In Seeing Like a State, James Scott writes that while we designate valuable plants as “crops” and some trees as “timber,” those that have not been assigned any value are called “underbrush” or “trash” trees. Animals that have utilitarian value are called “livestock” or “game” while others are called “varmints”.

As human activity depletes resources, these environmental movements have often been seen as eco-feminist in nature, for one can see the critical linkages between the domination of women and the domination of nature, both by masculinist forces. Vandana Shiva, environmental conservationist and eco-feminist thought leader writes, “We are either going to have a future where women lead the way to make peace with the Earth, or we are not going to have a human future at all.”

The construct of the planet as Mother Earth, a feminine entity, one that is naturally nurturing, but destroyed for profit is similar to venerating women as goddesses only to sexually violate them; a majority of the victims of human trafficking are women.

The politics of development

State-led developmental projects require extensive deforestation, and this leads to exploitative imposition of crop monocultures — that is, the alteration of forest ecology through replacement and the forced cultivation of trees such as teak and eucalyptus for profit. Monoculture has been criticised by environmentalists for causing disruptions in the food chain. Appiko founder Hegde has pointed out that elimination of forest cover renders these regions ecologically sensitive, incessant removal of forest cover leads to laterisation — that is, the conversion of arable forest land into rocky, mountainous patches, rendering the soil unfit for tree growth. Environmental degradation around the world follows similar patterns: land conversion for non-forest use, setting up of monocultures, building of dams, setting up of industries that pollute, and contamination of waterbodies — all of which lead to adverse climate change. In the process, many renewable resources are rendered non-renewable. An argument in favour of these developmental projects is that these are national resources and therefore the state can do whatever it pleases with them. Yet, it is precisely because they are national resources that one must understand that they belong to the indigenous people of the land who have been caring for it, often worshipping it.

Hegde says, “Women are impacted the greatest when the access to the forest is not provided.” Deforestation and excessive state control brings about a decrease in forest produce. Owing to the gendered division of labour, it becomes women’s responsibilities to procure fuel wood and fodder for livestock. Women, therefore, take great pride in participating in these social movements. They engage in community-level initiatives and organise cultural events to raise awareness about environmental causes.

In early March, the government introduced the new draft of the National Forest Policy with the aim of bringing at least one-third of India’s total geographical area under forest or tree cover; and, as welcome as that might seem, environmental activists criticise it for not being participatory and inviting private players. Environmental personhood is a new and upcoming legal concept. It refers to viewing natural resources as a person with rights that are violated by human activity. Recently, the Uttarakhand High Court assigned the “living entity” status to two rivers, the Ganga and Yamuna, for their protection and restoration. As laudable as these steps may be, without stringent anti-pollution laws, not much would change because denial of rights and their systematic violation is a moral issue and laws alone are insufficient.

The grassroots-level environmental movements are the ones that eventually pressurise state powers to bring about regulation. The success of movements such as Appiko is evident from the fact that laws now protect the region from the felling of green trees. Only dry, dead trees may be felled. The Chipko movement too was successful, for the Indira Gandhi government banned tree felling in the fragile Himalayan region for 15 years starting in 1980. Appiko has seen a snowball effect as it has gained popularity in other regions.

What started out as a small movement in Salkani village, Sirsi taluk, has spread to many districts not only within Karnataka but also to Wayanad, the hill district of Kerala, which had seen a drastic reduction in forest cover from 44 per cent in 1905 to nine per cent in 1984. Through the mobilisation of various groups, sustained awareness campaigns, community activities like folk dances, street plays and marches into the interior forest regions, the Appiko movement has taken on a larger goal — to save the Western Ghats. Right from the colonial era, these regions have been exploited owing to the rich deposits of iron, bauxite and manganese. Organised tree-felling and forest clearance for the cultivation of tea, coffee, teak and other for-profit crops and trees has made the region ecologically sensitive. In 2011, the Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel designated the entire Western Ghats as an ecologically sensitive area. Parts of the Western Ghats were declared a heritage site by the Unesco and have been recognised as one of the world’s 10 biodiversity hotspots. The Appiko movement goes by the slogan Ubsu (save), Belesu (grow) and Balasu (rational use) to spread awareness about the fragile state of the region’s ecology. It has come a long way since 1983 and, like other environmental movements, questions the state narrative of development and instead advocates for sustainable development, one where people, human activity and ecology remain in harmony.

Lavanya Shanbhogue Arvind is a feminist research scholar at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences

Source : https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/blink/know/whose-tress-are-they-anyway/article23522642.ece